Introduction to finding scientific literature

By Victor Malakov, Ellen Vos-Wisse

This is a collection of tips and ideas on finding and reading scientific literature. Many of us want to continue reading neuroscience literature in their topic of interest. That thirst for knowledge can be somewhat satiated by popular press, however I urge you to learn how to access the peer reviewed literature.

It’s real, it’s a true continuation of learning, for which you came to this course in the first place, and it’ll be at least partially quite accessible, after the introduction you have had during this course.

So if you want to explore some neuroscience topic further, or have a reference to an article that you want to read in full, the following might help you.

Tips for finding scientific literature

Tip 1. Start from the beginning.

Every chapter in the Neuroscience textbook comes with an extensive list of literature, including original papers and excellent reviews. Try to find them using the tips here. It’s a good start.

Tip 2. Use dedicated search engines

Search using dedicated search engines that index and search the scientific journals and books. Usually they are much better than just plain google. Here two most important openly available tools are:

- Google Scholar indexes everything that Google thinks is scientific.

- Pubmed indexes biology and medicine sources, which covers neuroscience quite well.

You can try to use Microsoft Academic Search too, which is Microsoft attempt to beat Google, or try to use any of the openly available databases listed here. In my experience Google Scholar and Pubmed are sufficient for most of our needs.

Tip 3. Finding full text.

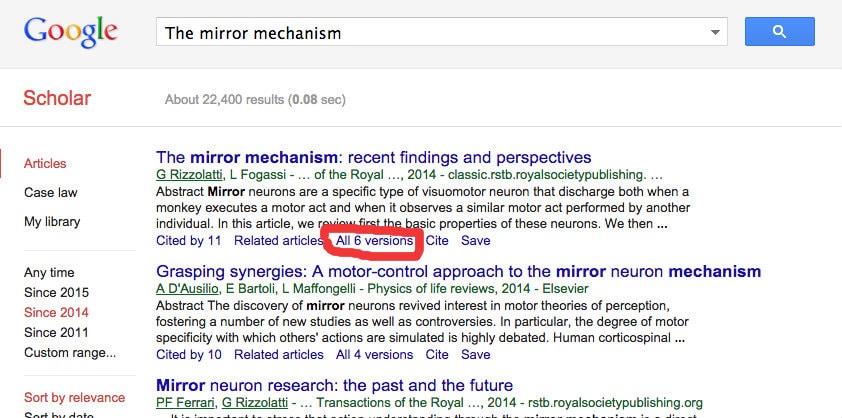

It is frustrating when you only find an abstract of your desired article. Google Scholar has a way of finding full text of the article even if it is not accessible from the journal website. If you see a link like “All 6 versions” (see below), click on it.

it will show you something like this:

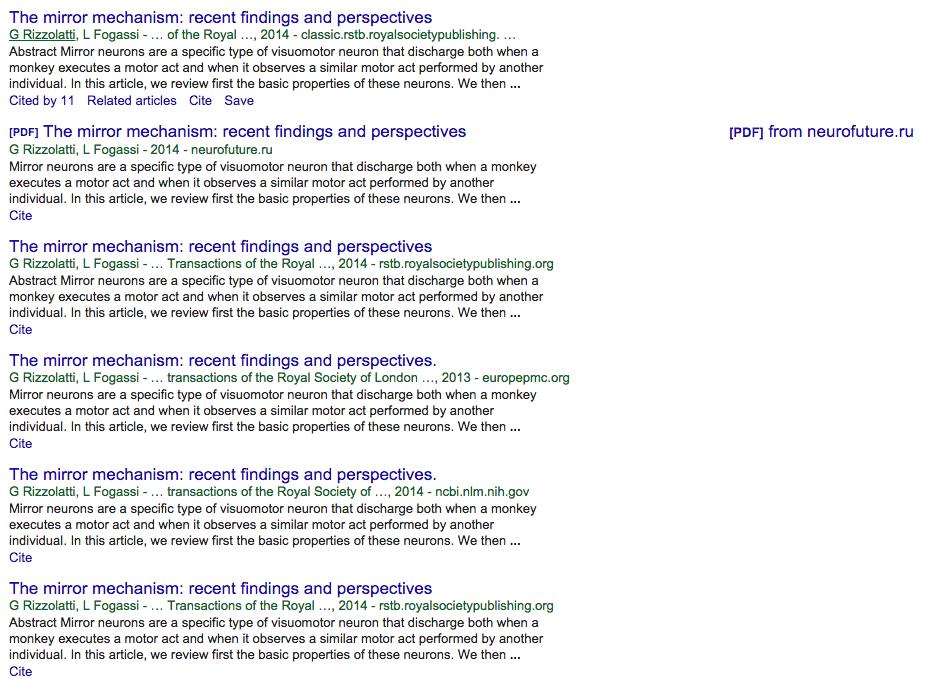

List of versions of an article

Google scholar found 6 mentioning of this article on the web, and one of them has a PDF, which you can click and read.

So how come these open access versions are available? In many cases authors themselves post them on their websites or the sites of their labs; often universities publish articles as part of their curriculum. In this example the article appears to be published on a site supporting a public lecture given by the author.

Sometimes you may come across a translation of the article in a different language (happens quite often with Spanish)

Tip 4: Open access

Some articles are published with open access. The good news is that there are journals that publish open access articles, and some are very good, here are some, to mention just a few:

- PLOS One Neuroscience

- Frontiers Neuroscience (and many other Frontiers publications!)

These days more and more articles even in the journals like Nature or Cell publish open access articles. One of the reasons for that is NIH Public Access policy.It forces author to open up their work. Most often it will be hosted on Pubmed, and Google Scholar will find it and link it accordingly.

This creates a ridiculous situation when the same article is both publicly available and accessible for a fee. What happens most often is that the open access version will be the Author’s manuscript, or uncorrected proof, without the final editing by the publisher. It will look weird, and often will have all the pictures and the diagrams in the end of the text, but it is better than nothing.

Tip 5. Articles behind a paywall

For those stubborn articles that are well hidden behind the paywall (or in obscure journal, or in the language you don’t understand).

Check other publications by the same authors or the same group. In these days when ‘publish or perish’ is the driving force of many research scientists, the same idea might get published several times during one year.

This is especially true of more recent publications. One of these works might well be in the open access and recapitulate the ideas you are searching for. A good way to find such articles is again, by going through articles that cite yours. Click on “cited by” in Google Scholar, or browse “Citations” or “Relevant articles” in Pubmed.

Tip 6. Different article types

Understand the article types. An article called an Original research, or even a letter or a brief report: these are primary sources.

They describe the original experiments or clinical cases, which could be very technical and difficult to read if you are not familiar with the field, but they are often the most exciting.

An article called a Review is a secondary source. The authors cite and review the original sources (and other reviews), and often try to draw conclusions, propose new theories, etc. These narrative-type articles might often serve as a good introduction to a topic which is new for you: after you read several reviews, it might be easier to understand the original research.

An article called Meta-analysis tries to systematically review the scientific literature to draw conclusions. They usually select dozens of articles, and systematically (often numerically) try to find a common conclusion from them. Meta-analyses on things like efficacy of a certain treatment or intervention method are generally held as the most reliable ‘scientific verdict’: because they accumulate the results not from one research group or article, but many.

Invited reviews, book chapters, Perspectives: these sort of articles are usually not dependent on peer review process, but are instead hanging on the reputation of their authors. You’re much more likely to find personal anecdotes, more ambitious formulation of concepts and theories in these.

Tip 7. Judging the credibility of an article.

Not every article you find will be an established fact. Peer review process is a good thing, but it’s not a guarantee of validity. There are articles published simply for the sake of vanity, and some are outright fraudulent, published to support a commercial interest for someone. So in order to navigate this world you will have to learn to distinguish good research from questionable from bad.

Here are some tips:

Check the citation numbers. Usually the higher the number, the better the article. Google Scholar will report higher numbers that either the Web Of Science or Scopus that are used in academia to measure citations, and Pubmed will report the lowest numbers: this is because Google Scholar includes non peer-reviewed sources and Pubmed is limited to just medicine-oriented publications.

The difference could appear huge: for instance, Alexander, DeLong & Strick 1986 review of the basal ganglia parallel loops is cited 6251 times by Google Scholar count and 762 by Pubmed’s at the time of writing.

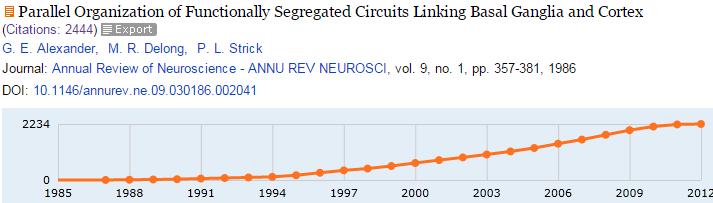

Citations numbers grow with time, of course. A recently published article will never have big numbers. Here you can use Microsoft Academic Search to display a nice chart of citations over time:

Citation numbers of a publication

But for our purposes of a layman’s judgment Google Scholar is probably sufficient. If an article is accumulating more than 100 citations a year, or has a total of more than 500 citations you can safely assume it is quite valid (or at least hotly debated)

And if you see thousands of citations, like in this case, you know it’s a classic. The example paper from Alexander et al. definitely is.

Browse the citations. All the search engines give you an easy access to all the sources citing yours. It’s a good idea to at least look through them to see what other people take out from this article; also at least some of them will probably treat the same topic, and you will learn from reading them. Maybe you’ll find a review that will give you more perspective.

Look who publishes Journals have reputations too. If Nature, or Science, or Cell, or Brain, some other well known journal is the publisher of your article, you can be reasonably assured the editors made some effort to ensure the peer review was valid and thorough.

But if an article is published in a journal that is not reputable, or is not really focused on the topic in question, that is a bad sign. However, sometimes real scientific breakthroughs are rejected in Nature and others. For example, the original mirror neuron report was rejected by Nature, and Rizzolatti only managed to publish it in Experimental Brain Research But click on the link and see that it’s now cited 2200+ times: so it’s a classic. (to their credit, Nature editors simply thought that the idea was too specialized to be of general interest, not that it was not credible. But they were hugely mistaken on the interest part:)

Check pubpeer.com. This is an open resource where other scientists comment on articles (without any permission from the publisher or authors, so it makes them quite sour). You’ll need to search by DOI there (you can easily find DOI reference in any recent publication). Most, almost all articles you check there will have 0 comments. But in rare case when you find something, you’ll be glad you did the check. See here. You can also occasionally read retractionwatch.com. Not to find something about your article, but to learn what it is that is considered bad research…

Tip 8. Deep exploration

Continue the deep exploration of your topic. Once you found an interesting article, try to find what other scientists wrote on the topic, or what the same author wrote in other articles.

You can do this by exploring the “cited by” articles on Google scholar or Pubmed. You can find a good review this way, or the most recent article on the topic.

Another good idea is to find a webpage of the lab or professor who wrote the article that interests you (in neuroscience articles the name of the lead author usually comes last in the list).

Tip 9. Take notes

When you read the articles that you find, always take notes. It is very rare that one article is really sufficient. You’ll find others. When you read those, your knowledge will expand, and maybe you’ll want to get back to the ones you started with. And believe me, it’s very frustrating to vaguely remember you’ve read somewhere something relevant, and not being able to find that research.

So take notes. Make a link (a reference) to the article you found, and briefly write down what was interesting, surprising, or useful in it. If you have questions, or don’t understand important parts of the article, it helps to write these down too. It will help you maybe a couple of weeks down the road.

There are applications, like Mendeley, specifically designed to handle references to the scientific literature. But frankly, any note-taking app will work wonderfully, as long as it is easy for you to use and has good search/tag/catalog functionality. Or you can try to post your notes on your blog, so other learners can help you or learn from you.

But taking notes (and returning to them) is really key.

Tip 10. Learn the vocabulary

t is very hard to find something if you don’t know the right terms or keywords. And frustratingly, sometimes when you think you know them, other scientists use different terminology, and their articles can fall through your search terms. For instance, if you are researching muscle proprioception, you may find less than half of what you are interested in if you only search for ‘proprioception’ as your keyword. Others refer to this as ‘kinesthesia’. And it is a good idea to try also ‘muscle spindles’ ‘golgi tendon organs’, ‘fusimotor’, ‘gamma motor’, ‘group Ia/II afferents’ and other terms that are related to your topic.

It’s not always easy to find the right terms, so it helps to start with good reviews (see Tip 1).

Another good idea is to find systematic reviews or meta-analysis articles (see Tip 6). These papers often describe the search terms they use to locate the articles they review, and it may give you an idea on how locate the relevant research in your topic. Or you can just replicate their search terms and read the articles this way.